Farallon Institute Newsletter - Winter 2023

2023 Concludes

Hello and thanks for reading our quarterly newsletter. Farallon Institute puts these newsletters together as a way to connect our community to what is happening in the Eastern Pacific Ocean as well as share the interesting marine research happening at Farallon Institute and beyond. In the past year we have highlighted the 2023 El Niño currently happening, how we use seabirds as indicators of climate change, all the goings on around the office, and much more.

If you enjoy what you read and want to support research for healthy and sustainable oceans, I’m asking you to consider making a tax-deductible donation to Farallon Institute. The science we do has a direct impact on ocean policies and ocean management and your donation will support our scientists as they conduct ground-breaking ocean research and serve on advisory committees helping manage marine protected areas, National Marine Sanctuaries, and State and Federal fisheries. Please reach out to me if you have any questions or want to learn more about the work we do…we’d love to connect and share Farallon Institute with you.

Sincerely,

Jeffrey Dorman | Executive Director

jdorman@faralloninstitute.org

State of the Ocean — Central-Northern California

We’ve officially moved into an El Niño climate event as of November, and its strength is forecasted to increase through the spring. Fortunately, California and the West Coast of the U.S. have been relatively spared from the warm waters the rest of the world is facing. Ocean conditions were a little warmer than average in late October and early November, but now have largely returned to normal for much of the coast.

In addition to warming waters, El Niño can also bring California a lot of rain! You may have noticed that the rainy season has begun, especially in Northern California and the Pacific Northwest, where there was large amounts of precipitation due to an atmospheric river at the beginning of December. El Niño historically means more rain along the West Coast, but things do fluctuate (see Figure 1 below). The outlook for this winter in California is for above average precipitation (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Winter precipitation for the strongest seven El Niño climate events since 1950. Source: NOAA Climate.

Figure 2. U.S. Seasonal outlook for precipitation, December 2023 to February 2024. Source: NOAA Climate Prediction Center, 4 Dec 2023.

Predicting risk of whale entanglements

Dungeness crab dinner for the holidays is a fantastic northern California tradition. In the last few years, however, fresh local Dungeness crab has been hard to come by as the commercial fishery opening has been delayed until after the holiday season. The reason for this is a complex ecological situation that spans micro-scale biotoxins to mega-scale humpback whales, and one that Farallon Institute is directly involved with helping to resolve.

One of the major considerations for the decision making about when to open and close the Dungeness crab commercial fishery is the presence of endangered humpback and blue whales in the nearshore crab fishing grounds. The crab pots set on the bottom of the ocean have long lines up to buoys on the surface of the water that whales can get tangled in and often results in their death. Commercial fishers, scientists, and managers in California work together to avoid this through an adaptive management process called RAMP (Risk Assessment and Mitigation Program) that considers the current risk of entanglement to whales and whether or not to open the fishing grounds based on this risk.

Farallon Institute is actively working on a project that will allow us to predict the risk of entanglement in central California by using models that indicate where whale prey, primarily krill and anchovy, are located. Understandably, whales follow these species, which fluctuate in their own distribution and abundance relative to environmental conditions. There is nothing easy about this sort of work but our scientists have had great success in answering these questions and this research will put a new tool in the hands of the RAMP team to help keep the crab fishery open when possible and also reduce entanglement of endangered whales.

This project is a great example of the type of work Farallon Institute does: marine research to inform sustainable management of resources. As a scientist there is nothing better than the work we do making a difference, and this project is on the frontlines of impact.

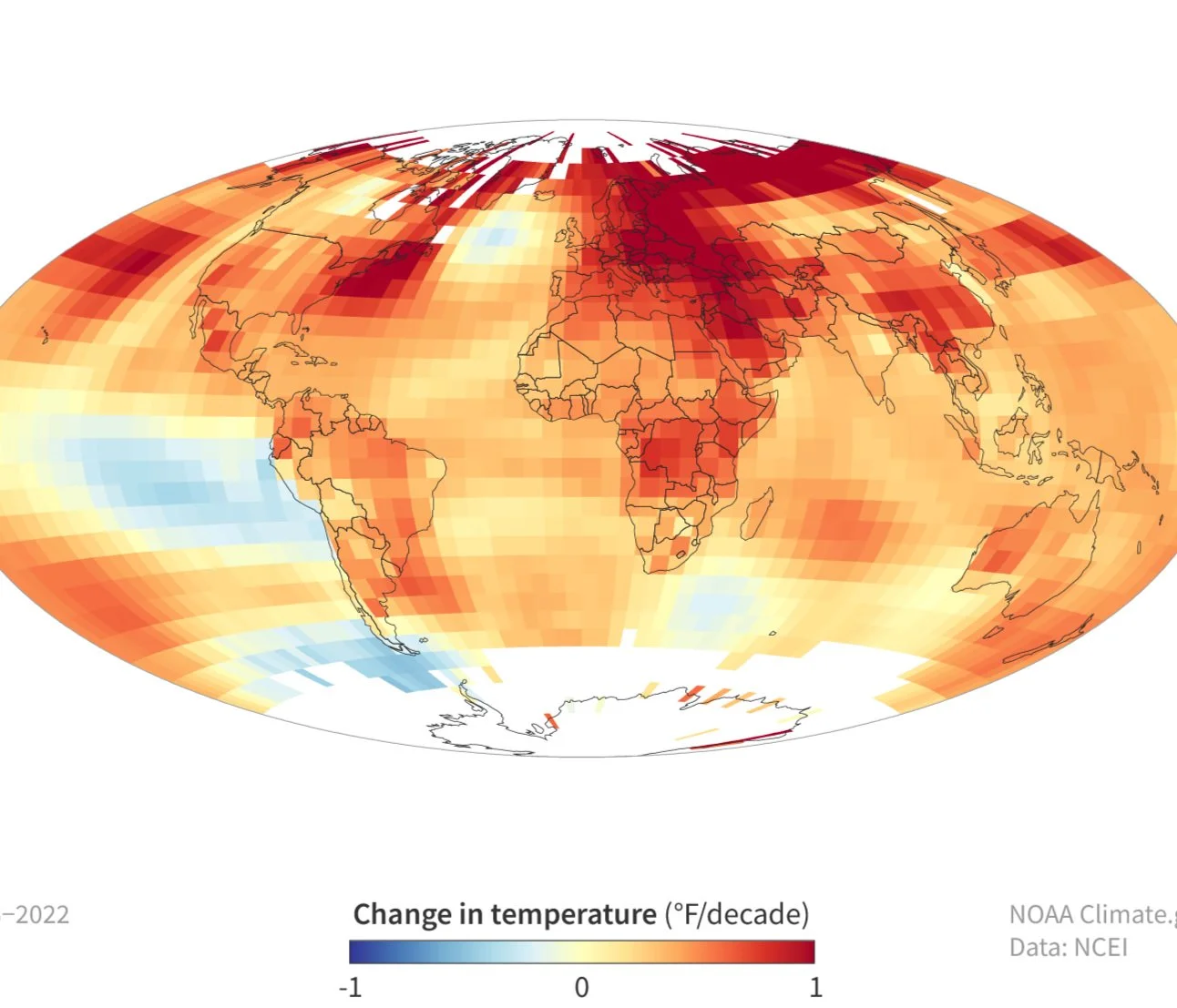

Trends in global average surface temperature between 1993 and 2022 in degrees Fahrenheit per decade. Most of the planet is warming (yellow, orange, red). Only a few locations, most of them in Southern Hemisphere oceans, cooled over this time period. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on data from NOAA Centers for Environmental Information.

COP28: What’s at stake in the “Global Stocktake”

As regular readers of the Farallon Institute newsletter State of the Ocean Reports know, the Eastern Pacific has continued to set records for temperature and other environmental variables in recent years. While we study how climate change is unfolding in our own backyard, scientists, politicians, diplomats, activists, and others have been gathering half a world away to plot a course to a cooler future on the global scale. The 28th Convention of the Parties (COP28) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change wrapped up last week in Dubai, UAE. The annual meeting brought together representatives from about 190 countries from around the world with a number of goals, most pertaining to the landmark Paris Climate Accords of COP23, when the world’s leaders agreed to limit average global warming to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, the maximum warming that will still allow us to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

Discussion at and about the COP has focused on several major themes. First, the conference was the conclusion of the “Global Stocktake”, a process to inventory international progress toward the goals set forth by the Paris Climate Accords. So far, results of the stocktake are not pretty: global warming exceeded the Paris threshold a few times in 2023, and national policies to combat climate change have currently set us on a path to 2.9°C warming as opposed to 1.5°C. Second, COP28 delegates attempted to grapple with how to lessen greenhouse gas atmospheric input by including language in the agreement to either “phase down” or “phase out” fossil fuels. In the end, delegates settled on language to “transition away from fossil fuels”, signaling an eventual end to fossil fuel-based economies. Unfortunately, the final language gave no indication of a timeline to achieve the transition. A major positive outcome of this COP, however, has been contributions made to a fund to pay for loss and damage associated with climate change in frontline, developing countries. While financial commitments from rich nations remain far behind the need, this is a belated first step. Finally, success has also been reached in limiting methane pollution, a greenhouse gas that is less abundant than CO2 but more powerful (28 times the warming potential of CO2!).

We can and should laud these accomplishments, but as the globe continues a steady rise in temperature and impacts, including here on the West Coast of North America, radical and likely disruptive innovations will be needed to meet the Paris agreement.